Church History

A Gateway Church on the Fife Pilgrim Way

The following is a short potted history of the parish church, much of it unearthed over recent years and not yet reflected in the history books. Archaeology continues within the building, still regularly giving up its secrets. It is clear from the high quality of the remaining stonework that this was one of Scotland’s great Romanesque architectural achievements and yet it has remained for many years in the shadow of its better known neighbouring buildings in Dunfermline and St Andrews. Could the tower, however, be Scotland’s oldest building still in regular use?

See here for opening time details.

|

Markinch Church - a mystery slowly revealing itself.

When King Edward I passed through Markinch in 1296 the tower that we see today was already more than 150 years old, dating back to the early decades of the 1100s. His French chronicler referred to it as a "moustier" or minster, and recent research including the use of ground penetrating radar has shown that the building was indeed of significant size, although never a minster in the usual sense of the word. The scribe also seemed puzzled as to how few houses there were around it, an anomaly that has been unexplained until recent times. The reason is gradually becoming clearer as work continues on an archaeological exploration of the building's early 12th century remains. Perhaps a large church in the middle of a sparsely populated area such as 12th century Markinch can best be explained if it was originally designed to be a fortified castle-church used only occasionally when the earl visited to make judgements on the hill at Dalginch. |

|

Castle or Church?

With walls more than a metre thick, the tower at the western end of the building is more like a castle than a church and recent archaeology seems to confirm this dual function. The bell tower would have been a stark statement of lordly power, complete with delicately carved frieze motif of diamond shapes. Even the bell chamber itself with its elegant external columns and inward-facing arches may have had a function beyond that of simply housing a bell. The great western arch was also designed to impress. A charter document was sealed in Markinch by Earl David, brother of the King of Scots around 1174, and there is a strong likelihood that the event took place within the walls of Markinch Church. Duncan Earl of Fife was the principal witness.

|

|

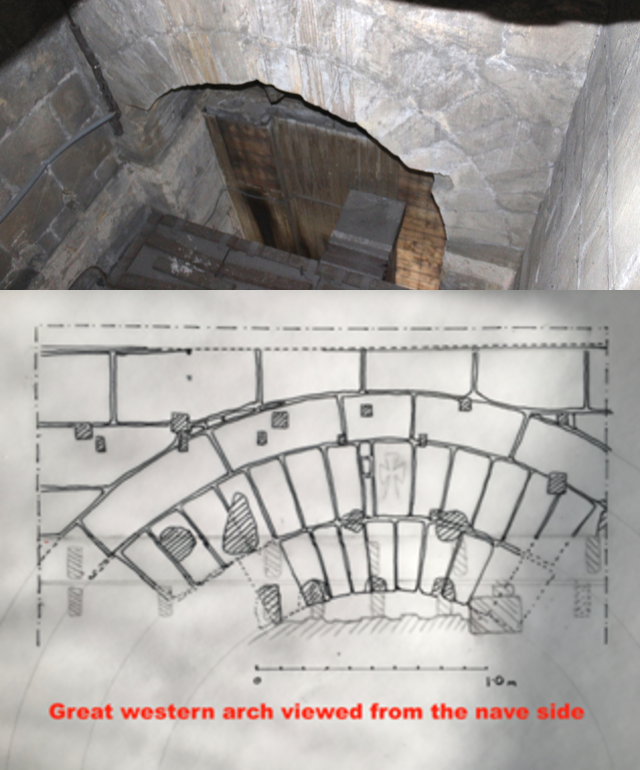

Markinch Church in the Time of MacBeth

At the eastern end would have been a chancel, no doubt originally coming under the control of the Bishop. A section of its star-decorated arch was discovered in the graveyard, seen above. It was built on the site of an even more ancient church referred to in a charter dating back to the time of King MacBeth, and was part of a series of gifts to the Culdee monks of Loch Leven. This grant was possibly part of a package of gifts arranged by MacBeth himself, his wife Gruoch and the Bishop of St Andrews to ensure that prayers were said for the king's soul during his pilgrimage to Rome in the middle of the 11th century. This older church may have been used as a place of worship during the construction phase of the existing Norman style tower, a project that would have taken several years to complete. The existing east-and north-facing doors in the tower are 18th century insertions, and the original structure may only have been accessible from inside a solidly constructed nave through the great western arch. This arch was a surprise when it was rediscovered embedded in the post-Reformation walls a few years ago. Its great height can be appreciated from the existing balcony where archaeological work to carefully remove 19th century plaster work is underway. |

|

Dalginch - Seat of Judgement

This emphasis upon defence is perhaps unsurprising given that the building owes its existence to one of the most powerful families in Scotland, the MacDuffs of Fife. The Earl of Fife and the MacDuff clan chief (sometimes both roles were combined) would have regularly visited the area to pronounce judgement on the nearby moot hill at Dalginch (Northhall). They would have needed a safe place to reside when surrounded by potential enemies at such an important event. The kingship of Scotland was also still in dispute, with the MacDuff lineage having a potential claim to the throne. This claim was wisely never pursued, the family preferring the role of king-makers rather than kings. The building seems therefore to have had both secular and ecclesiastical uses, and putlog holes, as can be seen either side of the window here and originally used for scaffolding, may have been reused to create a projecting balcony or "hourding" as an added defensive feature. Defensible "tower-naves" were not uncommon prior to the Norman period both north and south of the existing border, and the "great western tower" may have been a later development. In England most of the hybrid, Anglo-Saxon structures were rebuilt as churches in the Norman style but usually with a purely ecclesiastical function. Indeed it required a papal edict of 1123 to outlaw the practice of constructing defensive churches. Whether before or after that date, the MacDuffs seem to have used Norman technology to create a very substantial building, complete with combined lookout post and safe room at the top, private chapel and possibly accommodation over the nave. The function of the belfry level has still to be determined. This configuration seems to reflect in stone a pre-Norman architectural form that may have been constructed of timber. Memories of a massacre a couple of generations earlier would still have been strong when fifty of the kinsmen related to Gruoch's first husband were burned to death in what was presumably a wooden structure. In fact scorch marks and other damage around the north western corner of Markinch tower possibly indicate an unsuccessful attempt to attack. |

|

A Gift to the Priory

In the 1160s when it was a few decades old the building was granted to the Priory of St Andrews with the Bishop of St Andrews and two members of the powerful MacDuff family as co-grantors. From that time on the religious aspect of the building would have been to the fore as the MacDuffs transferred their focus of interest to Cupar, Culross Abbey and other parts of Scotland where they held land. In the 1240s the building was rededicated to St John the Baptist, but St Drostan's fair day, just before Christmas, was celebrated until the 19th century. Earl Malcolm donated a portion of land to the Priory in the early 13th century (now Mansefield - seen right) and the Valognes family, probably vassals of the Earl, granted more land next to the church, the glebe or minister's meadows, in the late 13th century. |

|

The Marks of the Builders

The indications from recent research show that the building was once decorated in the Norman style perhaps using masons from Normandy as well as other parts of the island of Britain. They were paid on a piecework basis as we have around 800 surviving stonemasons marks. The stones were lifted up the tower using a large wheel winch whose spindle slots can still be seen in the ground floor walls. The solidity of the building was assured by a clear instruction cut into a stone that bears the mark of the master mason. It demonstrates clearly the principle of half bonding, the regular overlapping technique that gives modern brick buildings their strength. Although no definitive traces have yet been found, the interior of the nave was probably brightly painted. Traces of the artistry of the carpenters, metal workers and other craftsmen (and perhaps women artists) has now almost disappeared leaving only the stone to be interpreted after nearly 900 years. |

|

The Lost Arch

The massive double voussoir arch that was discovered between the tower and the nave was previously hidden within the post-Reformation masonry and once had a decorated frieze on the side facing into the nave. However, that has been chiselled off leaving only a simple cross that seems to have been carved on the keystone by the master mason. Its design may incorporate his personal banker mark. Both the north and the south walls of the original nave have been demolished in widening projects, their stone being recycled into the 17th and 19th century reconstructions. Traces of the original star pattern arch can be seen incorporated into the southern wall. These match up with a section of the chancel arch found during a recent survey of the graveyard stones. It is a design fashionable around 1100 and found from Normandy to Trondheim with interesting local examples at Dunfermline, Legerwood near Lauder and Ormiston in East Lothian. |

|

An Upper Chamber?

Although investigations are not yet complete it seems that a doorway led from the first level of the tower into a chamber above the nave. This is currently being interpreted as a domestic space linked to rooms in the tower that also had a domestic function when originally planned. Later, under the control of the Priory the ecclesiastical functions of the building were given greater emphasis and this space may have been used for storage. Much more comparative work with similar buildings requires to be done on this aspect. The small room at the top of the tower (now behind the clock face) may have been used for the storage of charters and valuables which may have included precious relics. Given the sparse local population it is not clear whether the belfry was designed to house a large bell, and the room could once have had a variety of domestic functions. Each opening has an inward looking segmented arch. |

|

A Pilgrimage Church

Throughout the later medieval period, references to Markinch parish occur sporadically in the Vatican archives as successive vicars sought career advancement in Rome. Pilgrims would have stopped off at the church on their way from Dunfermline to St Andrews but we know little of whether either St Drostan or St John the Baptist had any special spiritual significance to them. Few local records or artefacts remain to tell the tale of the church through these long years of war and pestilence. Only a single carved plinth in the form of a dragon that was rescued from a neighbouring garden remains as evidence of a once richly decorated Roman Catholic interior. It is likely that this was a shelf for a carved wooden saint installed by Prior John Hepburn. As Rector in the early 1500s Hepburn installed his own family coat of arms at the eastern end of the building. This may have been part of an improvement programme designed to make the church more attractive to pilgrims at a time when pilgrimage to St Andrews was on the wane. Markinch was at the centre of the Reformation in Scotland with many men losing their lives in the bitter wars of the mid 17th century. Much of the evidence of damage done to the building around this time is hidden behind the elegant 19th century panelling and plasterwork that we see today. All traces of the highly crafted effigies and brass work above the graves of Cardinal Beaton's parents have gone. A local tradition has it that he was buried secretly beneath the church. The quality of the Beaton family tomb would have been of the highest order, commissioned by Beaton from Andrew Mansioun a most skilled Renaissance craftsman but not a trace remains. |

|

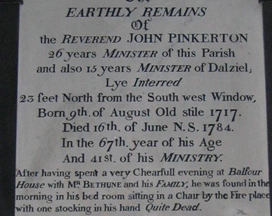

New Presbyterian Heritors and a Minister’s Strange Death

The post-Reformation period was dominated by the Earls of Leven, later the Leslie-Melvilles. Their family tomb was converted into a vestibule when they left the area in the 19th century. Their successors as principal heritors were the Balfours of Balbirnie who have contributed greatly to the upkeep of the modern building. All the family tombs under the church were removed in the 19th century and only a single grave remains, a curious feature describing the strange death of a former minister after a "cheerful evening" at Balfour House, the ancestral seat of the Beatons (Bethunes). |

|

Modern Times and a Complete Refurbishment

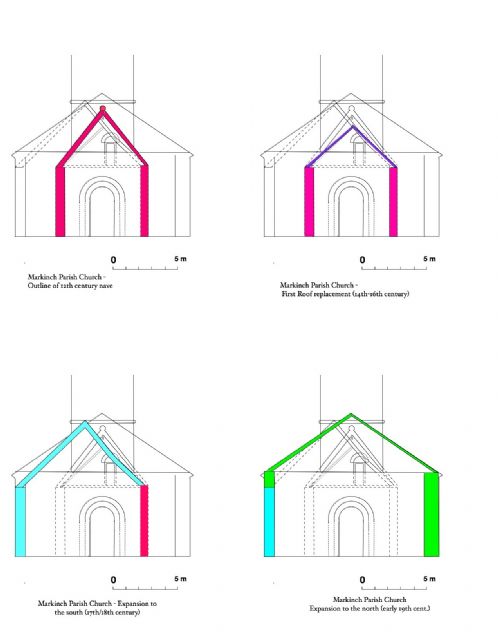

The population of Markinch expanded along with the growing linen and woollen industries in the town and the church was substantially widened during the late 17th century, the early 19th century and again in the 1880s. This rebuilding further eroded the medieval fabric but the old 12th century gable walls of the nave and chancel remain along with the tower which was repurposed for a while as a jail, then a clock tower and latterly as a housing for the organ bellows. The lavish use of pine on the panelling and pews of the present day church reflects its Georgian and Victorian heritage. The continuous repurposing of the tower over nearly 900 years is a feature making it likely to be Scotland's oldest building still in active use today. It may even be slightly older than its larger neighbour, St Rules in St Andrews, both towers demonstrating supreme architectural craftsmanship. Although their functions were very different, one perhaps being built partly to outshine the other in height and splendour. Records show that the earl and the bishop were powerful local rivals, both turning up to a boundary dispute around 1128, each with a retinue of armed men. This enmity may have been expressed in stone around this time although work continues to pin down a more precise construction date. |

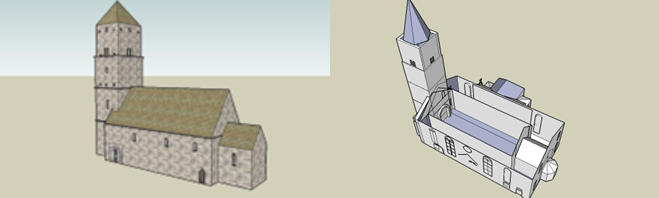

The first model shows how the church may have looked in the early 12th century and the second illustrates the progressive widening of the building enveloping the former nave and chancel. These stages are clearly etched on the eastern side of the tower inside the modern loft space. The small door entering into the original upper chamber is also shown. |

With many thanks to Bruce F. Manson